University of Mary Campus is Site of Historic Fight Between Native Warriors and U.S. Military

Public and media invited to presentation and historic event Friday, October 11, as University of Mary, tribal members and the National Guard ceremoniously mark a forgotten Dakota Territory battle

BISMARCK, ND — Dakota Goodhouse, a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Nation, remembers the moment like it was yesterday. In 2004, he watched as surveyors used their shovels to poke holes into the hill east of University of Mary alongside its entrances where a new segment of 1804 Highway would be built.

“I didn’t need the physical evidence, but to see that first shovel full of arrowheads made it more real,” recalls Goodhouse, a 2003 University of Mary alum and Native American Studies professor at United Tribes Technical College. “It made the oral record real since the physical evidence was there.”

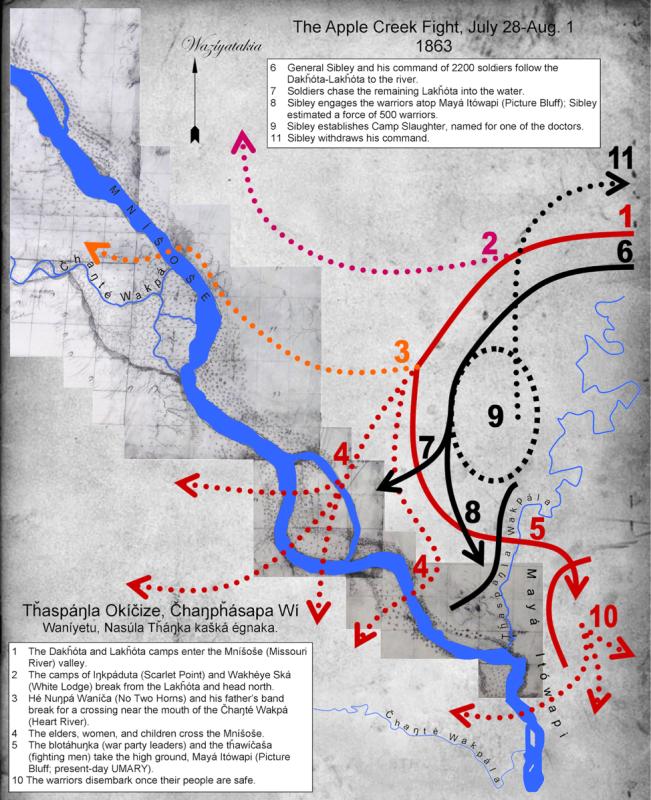

Those arrowheads belonged to warriors of the Dakota and Lakota people who fought and defended the very same hill against approximately 3,000 U.S. military soldiers under the command of General Henry Sibley in 1863 during the Apple Creek Conflict. The skirmish marked the end of a two-week running battle the two sides had from Big Mound, near present-day Tappen, ND, southwest to Apple Creek.

According to Goodhouse, the hill where present-day University of Mary sets was known in native languages 156 years ago as “The Bluff Where They Dig for Paint,” because of sediments inside caves along the bluff when mixed with bear grease would make paint. Its majestic view overlooks the Apple Creek confluence and will be the site of the ceremony Friday, October 11 at 11:30 a.m. commemorating that fight, with representatives from various tribes, the National Guard and University of Mary in attendance. This event is preceded by a convocation from 10 a.m. until 10:50 a.m. in Butler Auditorium (inside the Gary Tharaldson School of Business) on campus hosted by the University of Mary and presented by Goodhouse, detailing the Apple Creek Fight. Both events are free and open to the public.

“The Apple Creek Fight lasted from July 30, to August 1, 1863,” described Goodhouse. “Sibley’s command was unable to take the hill or any prisoners and some of his men were ambushed in the middle of the night. On the last day of the fight, Sibley withdrew from the field. This was the only native fight of the 1863-1864 Punitive Campaigns in which the Dakota and Lakota chose the battlefield, met their aggressor, and held them off until they withdrew.”

According to Goodhouse and various scholarly accounts, this running battle began as a masterful retreat on July 24, 1863, across hilly terrain in a sinuous line back and forth across streams. This constant crossing, in effect, caused Sibley to lag behind enough for the Dakota and Lakota to gain enough lead time that the women, children and elders could navigate their crossing where the Apple Creek converges with the Missouri River. That critical crossing came on July 29, 1863. The warriors rallied together, perhaps under the leadership of Gall, Sitting Bull, Walks in Red, Black Eyes, No Two Horns and alongside Dakota leaders like Scarlet Point, White Lodge, Two Bear , Standing Bull and many others and took the high ground atop The Bluff Where They Dig for Paint.

“About 500 warriors took command of Mayá Owáse K’ápi—The Bluff Where They Dig for Paint,” recalled Goodhouse while talking with Dr. Mike Taylor, associate professor of education at University of Mary, as they walked along that very same soil at Mary where his ancestors fought to defend the hill.

“The women, children, and elders crossed the Missouri River (Mnišóše) in various places, from where the Northern Pacific Railway Bridge was built, to where the Apple Creek (Thaspáŋna Wakpána) joins the Mnišóše,” recalled Goodhouse as he pointed from the Sageway path atop the bluff on campus to the vast Missouri River as it meanders below within the valley. “Mothers held themselves and their children under water by holding onto stones and breathed through reeds to escape the soldiers. Many drowned, their bodies floated away with the current. Many emerged from the river onto Burnt Boat Island, later called Sibley Island. Those who made the crossing used mirrors and flashed sunlight to the warriors on Mayá Owáse K’ápi, letting them know they made it.”

Goodhouse continued to walk with Taylor along Sageway path on campus atop The Bluff Where They Dig for Paint and tell more stories, or counts, of what led to that three-day fight and those arrowheads buried in the prairie soil for over 150 years.

A month earlier, in June of 1863, leading up to this conflict, Sibley received orders to march west into Dakota Territory and engage any Sioux Indians in retaliation for the 1862 Minnesota Dakota Conflict. The Santee tribe were chased and fled west from Minnesota into Dakota Territory and coincidently met up with the Dakota and Lakota tribes — who had nothing to do with what happened in Minnesota, but because of their close proximity to each other — got caught up in the conflict.

“This conflict was four-and-a-half times longer than the Battle of Little Big Horn and twice as large in terms of U.S. Military and Native American involvement,” added Taylor. “By multiple accounts, the Dakota and Lakota were outnumbered 4-to-1 by Sibley’s forces as they tried to overtake the high ground. That ratio could have been much higher in favor of the military had General Sully not been about a week late to the Battle of Apple Creek—and missed it completely. Many skirmishes happened around current-day Sibley Park during that conflict, including many accounts of Sitting Bull, with other warriors, taking horses from soldiers.”

“This clear victory became entirely overshadowed by the tragedies of Whitestone Hill, the Killdeer Mountain Conflict, and the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876,” added Goodhouse.

According to Goodhouse and Taylor, while The Bluff Where They Dig for Paint that Mary’s campus sits atop played a significant role in that victory, the Battle of Apple Creek also adds to the legend of North Dakota, and to U.S. and Native American history—one that is often neglected or continually overlooked by many historians and scholars.